China is the world’s second-largest economy after the United States by gross domestic product (GDP), and a top U.S. trading partner. Over the past four decades, China has transformed from a largely agrarian society into a global manufacturing hub and a central player in international supply chains, driven by rapid urbanization, large-scale infrastructure investment, rapid productivity growth, unprecedented state support to industry, and investment and export-led growth.

China’s gross national income (GNI per capita) in 2023 was $13,390 according to World Bank statistics, placing it at the top end of the World Bank’s upper-middle income bracket. If current trends continue, China’s GNI per capita will exceed the World Bank’s upper-income threshold of $14,006 before the end of the decade. China’s per capita income growth reflects significant GDP growth over the last four decades. Over the same timeframe, however, data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics indicate income inequality within China has remained high. China Family Panel Studies data show income inequality has actually sharply increased, particularly in the last decade.

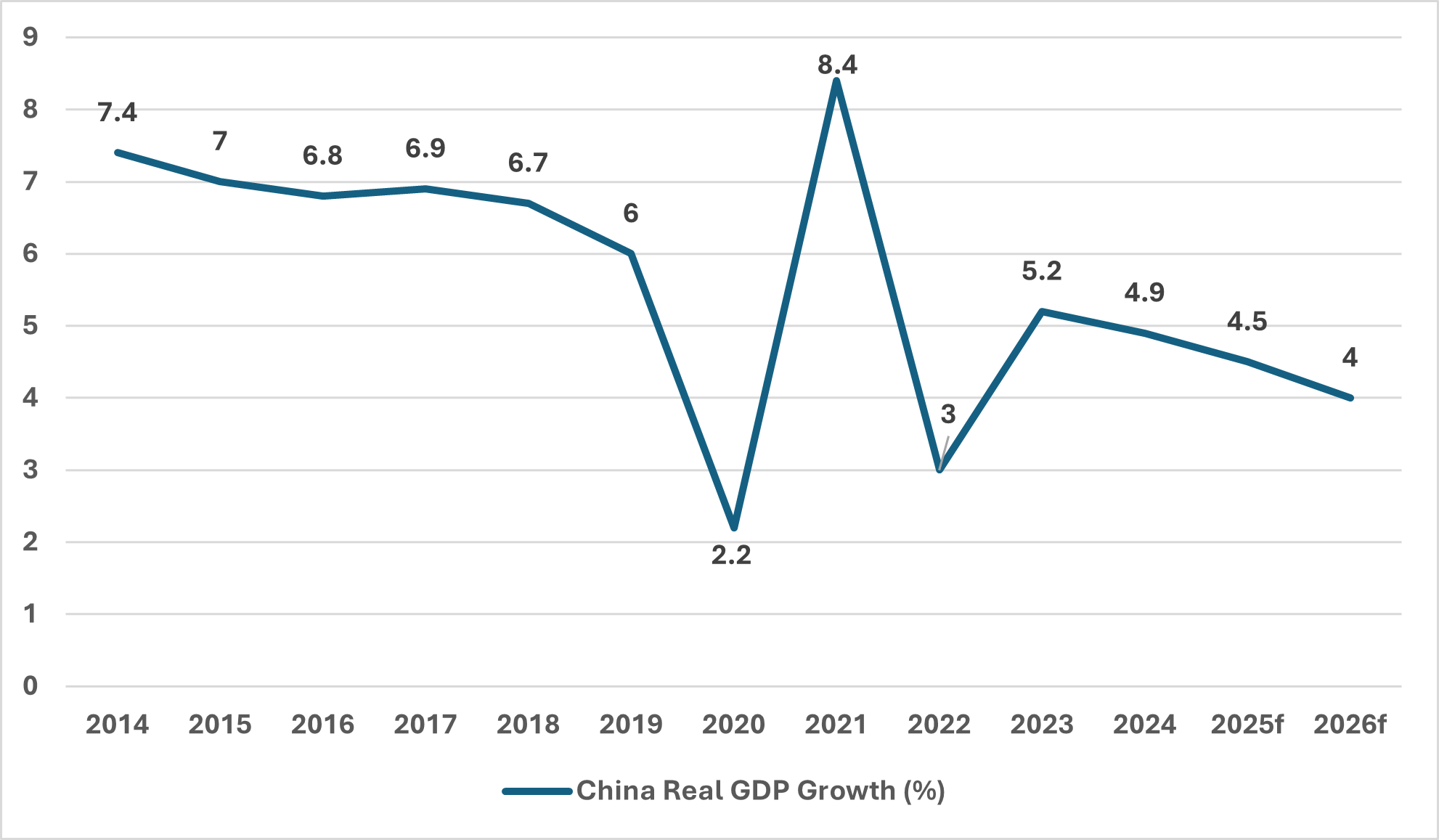

China’s economic trajectory is entering a more complex phase, marked by slower growth and deeper structural headwinds. China’s slowing growth trajectory was exacerbated by the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and an ongoing real estate correction. The country posted 5.0 percent GDP growth in 2024, but persistent domestic challenges including weak consumer spending, structural imbalances, and overreliance on export- and investment-led growth have kept growth below past highs. The World Bank projects 4.5 percent growth for 2025 (the IMF projection is 4.6 percent), despite a lagging property sector, which has represented a significant portion of the country’s GDP. Beyond 2025, long-term pressures such as declining productivity, an aging population, and continued reliance on investment over consumption threaten to further slow momentum. Without substantial reform, the IMF forecasts China’s growth could decline to 3.3 percent by 2029, a sharp drop from the rapid expansion seen in the 2000s and early 2010s.

Chart 1: China Real GDP Growth (Percent)

Chart 1 description: China’s Real GDP Growth was 7.4 percent in 2014, trended downward for a few years, and peaked at 8.4 percent in 2021. In 2024, growth was 5 percent and is projected for 4.5 percent or slightly higher for 2025.

Source: World Bank, China Economic Update, December 2024

Note: f = forecast (baseline)

In response to slowing growth and structural pressures, the Chinese government has introduced various fiscal measures to boost domestic consumption, support the manufacturing sector, and stabilize the property sector including subsidies for purchases of vehicles, major appliances, and industrial equipment; easing of key lending rates; and special-purpose bond issuances to support infrastructure projects. These measures have helped place a floor under China’s GDP growth, but domestic and international analysts have noted the policies have been unable to reverse negative consumer and investor sentiment and do not address the deep structural issues hindering sustainable economic growth. The IMF has called for comprehensive reforms in social safety nets, fiscal rebalancing, and services liberalization to foster sustainable, consumption-driven growth. Similarly, the World Bank’s 2024 China Economic Update noted the limited impact of current policies on private investment and household confidence, urging structural reforms in the labor market, pensions, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to rebuild trust and drive sustainable demand. It also highlighted growing fiscal pressures at the local government level, which restrict investment-led stimulus.

China remained one of the world’s most closed major economies, ranking 88th out of 104 countries surveyed in the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development’s (OECD) December 2024 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) restrictiveness index and last among major economies on direct investment openness in the Atlantic Council’s 2024 Pathfinder Scorecard. Inbound FDI fell 27.1 percent to $114.8 billion in 2024, according to statistics from China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). Industry contacts attributed the decline to a host of factors, including “promise fatigue” following repeated failures of China’s leadership to fulfill commitments to improve the foreign investment environment, China’s declining economic growth outlook, and concerns about the ability to repatriate capital committed to investments in China.

U.S. and other foreign companies reported increased anxiety about operating in the Chinese economy for a host of reasons, including a sluggish Chinese economy, a restrictive business environment, and the Chinese government’s increasingly aggressive use of legal and regulatory tools to target foreign individuals and companies as diplomatic leverage or for crossing the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) political redlines.

China remains a complex and often difficult operating environment for international firms. One of the central challenges is the Chinese government’s continued reliance on a state-led, non-market economic model. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is intensifying efforts to promote “self-reliance” in strategic sectors such as advanced manufacturing, critical minerals, and high technology often at the expense of foreign firms. According to the 2024 U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance, China’s industrial policies have become increasingly predatory, designed to displace foreign competitors and achieve dominance in targeted industries both within China and globally.

China’s central, provincial, and municipal governments all use a wide array of non-market tools to support domestic firms and disadvantage foreign ones, including large-scale subsidies, forced technology transfer, market access restrictions, discriminatory regulations, and preferential treatment for state-owned and politically connected enterprises. These interventions often result in predatory pricing and bidding strategies that allow Chinese firms to undercut competitors, dominate global supply chains, and distort fair competition.

In addition to these systemic policy challenges, rising labor costs and intense competition from increasingly capable domestic companies have made entering the market more challenging than in previous years. Most U.S. companies operating successfully in China today established their presence years or decades ago and have built deep local relationships, strong brand recognition, and specialized capabilities.

Companies considering the China market should weigh these structural challenges carefully, seek trusted local partners, and ensure robust due diligence and risk management strategies. In addition, U.S.-China commercial relations remain a key area of uncertainty. Businesses should closely monitor policy developments and assess the potential impact of shifting trade dynamics on their cost structures, supply chains, and market access strategies.

U.S. China Trade Relationship

As of 2024, China ranked as the fourth-largest U.S. goods trading partner after Mexico, Canada, and the European Union (counted as a single bloc) according to the Congressional Research Service and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. China remains a key destination for U.S. exports such as aircraft, agricultural products, semiconductor equipment and chips, gas turbines, and medical devices. It is also a major source of U.S. consumer goods and intermediate inputs – many of which are critically important to U.S. and global supply chains, such as rare earth elements and active pharmaceutical ingredients.

In 2017, U.S. national security policy formally identified China as a strategic competitor. In 2020, the U.S. Government signed the Phase One trade agreement with China to address to address many of China’s long standing market distorting and discriminatory practices.

In January 2025, President Trump introduced the America First Trade Policy, launching a comprehensive review of U.S. trade policy with a particular focus on China. The overarching goal of the policy is to bolster U.S. economic resilience, technological leadership, and industrial strength while pursuing reciprocal and balanced trade with U.S. trade partners. (For the full summary please see https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/america-first-trade-policy/ On April 3, 2025, the Administration published an executive summary of the review submitted to President Trump, which articulates the United States’ strategic approach to trade, emphasizing economic and national security.

Regarding China, the report addressed several key points:

- Trade Deficit: The report notes China is a significant contributor to the 2024 U.S. trade deficit in goods of $1.2 trillion. The report underscores the need for balanced trade to protect American industries.

- Unfair Trade Practices: It identifies China’s non-reciprocal and distortive trade practices and makes recommendations for potential new Section 301 actions that may be warranted.

- Phase One Agreement Compliance: The report evaluates China’s adherence to the Phase One Agreement and suggests measures to ensure compliance.

- Tariff Measures: Proposals include imposing tariffs on certain imports and creating an External Revenue Service to optimize tariff collection.

The overarching goal is to bolster U.S. economic resilience, technological leadership, and industrial strength while addressing challenges posed by China’s trade policies. (For the full summary please see https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/america-first-trade-policy/.

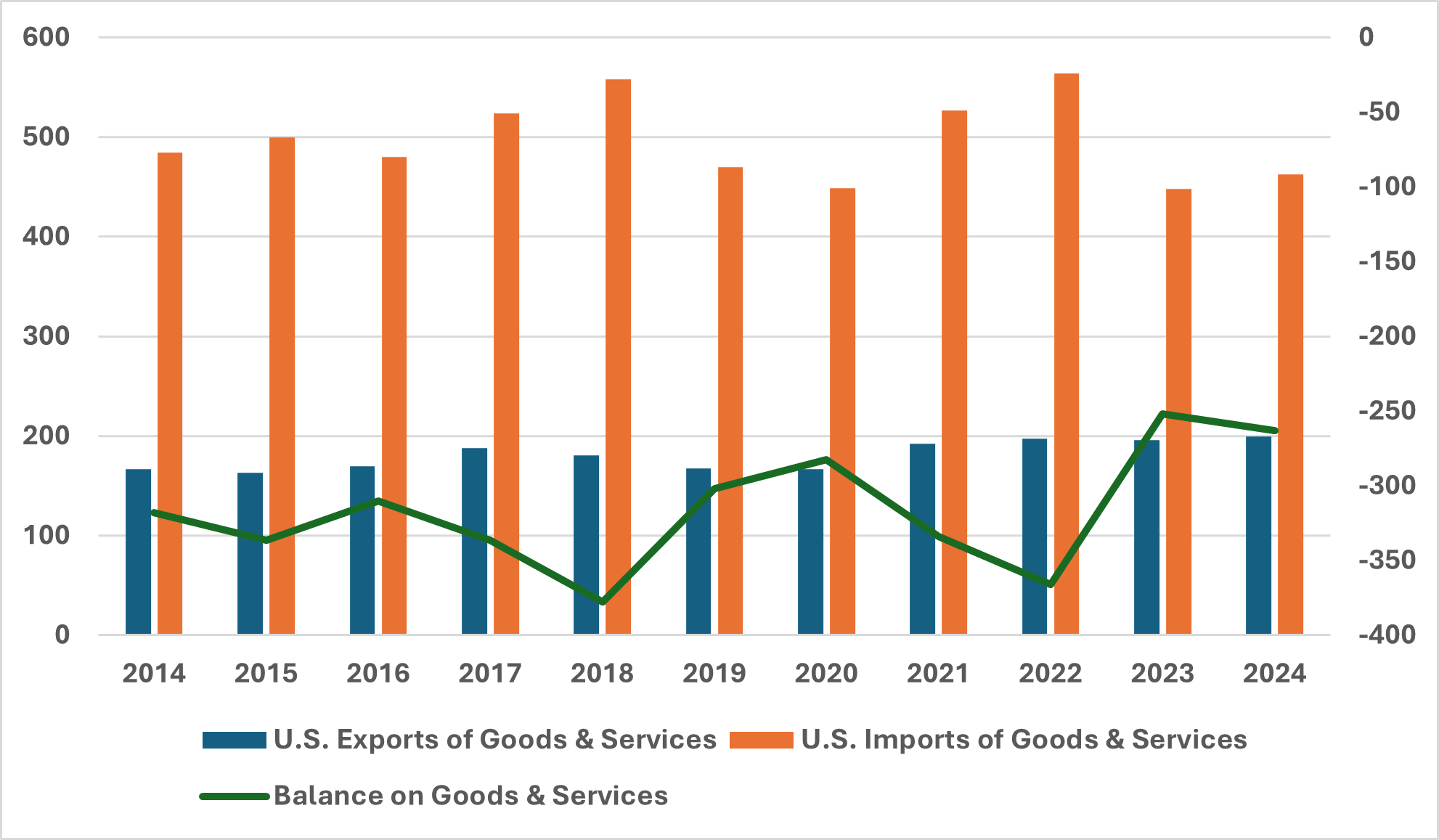

In 2024, U.S. exports of goods and services to China totaled $199.2 billion, a 1.8 percent increase from 2023, while imports from China reached $462.5 billion, up 3.3 percent. This widened the U.S. trade deficit with China to $263.3 billion. According to U.S. Census data (Seasonally Adjusted, BOP Basis), total U.S. goods trade with China was an estimated $584.3 billion in 2024. U.S. goods exports to China stood at $144.5 billion, down 2.85 percent ($4.2 billion) from 2023, while goods imports totaled $439.7 billion, up 2.85 percent ($12.22 billion). The goods trade deficit alone was $295.1 billion in 2024, a 5.91 percent increase ($16.46 billion) from the previous year.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, top U.S. goods exports to China in 2024 included oilseeds and grains (primarily soybeans), oil and gas, aerospace products and parts, pharmaceuticals and medicines, semiconductors and other electronic components, navigational/medical/control instruments, basic chemicals, resins, synthetic rubbers, motor vehicles, and industrial machinery.

Top U.S. imports from China included communications and computer equipment, electrical components, household appliances, plastic products, apparel, motor vehicle parts, semiconductors, and general-purpose machinery. In the services sector, China accounted for 4.9 percent ($54.6 billion) of U.S. services exports and 2.8 percent ($22.8 billion) of imports in 2024, according to BEA data. Leading U.S. services exports to China in 2023 (latest available data) included: Travel ($20.2 billion for all purposes, of which Education-related Travel was $14.2 billion), Charges for the Use of Intellectual Property ($7.1 billion), Financial Services ($4.1 billion), and Transport ($3.9 billion). For more information, visit BEA’s International Transactions, International Services, and International Investment Position Tables.

Chart 2: U.S.-China Trade Balance (US$ Billions)

Chart 2 description: The U.S. trade deficit was –$318.2 billion in 2014, peaked at –$377.5 billion in 2018, and narrowed to –$262.2 billion in 2024.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Table 1: Top U.S. Goods Exports to China in 2024 (US$ billions)

Top U.S. Goods Exports | 2024 Dollar Volume (Billions) | % Change from 2020 |

Oilseeds & Grains | $14.9 | -12.4 |

Oil & Gas | $12.3 | 32.5 |

Aerospace Products & Parts | $11.5 | 162.7 |

Pharmaceuticals & Medicines | $10.8 | 83.9 |

Semiconductors & Other Electronic Components | $10.5 | -12.8 |

Navigational/Medical/Control Instrument | $6.1 | 2.6 |

Basic Chemicals | $5.9 | 31.5 |

Resin, Synthetic Rubber, And Artificial Synthetic | $5.3 | 41.1 |

Motor Vehicles | $4.8 | -19.9 |

Industrial Machinery | $4.5 | -18.9 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (TradeStats Express)

Table 2: Top U.S. Goods Imports from China in 2024 (US$ billions)

Top U.S. Goods Imports | 2024 Dollar Volume (Billions) | % Change from 2020 |

Communications Equipment | $51.9 | -6.2 |

Computer Equipment | $42.4 | -28.2 |

Miscellaneous Manufactured Commodities | $40.4 | 16.1 |

Electrical Equipment & Components | $26.3 | 137.1 |

Household Appliances & Misc Machines | $18.5 | 2.3 |

Plastics Products | $16.8 | -5.0 |

Apparel | $14.5 | 10.3 |

Motor Vehicle Parts | $12.6 | 23.6 |

Semiconductors & Other Electronic Components | $12.2 | 12.7 |

Other General-Purpose Machinery | $11.5 | 5.0 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (TradeStats Express)

China’s Industrial Policy

China continues to implement a wide array of state-led industrial plans and related policies that seek to limit market access for imported goods, foreign manufacturers, and services suppliers, while offering extensive government guidance, subsidies, tax incentives, land grants, preferential credit, implicit and other guarantees, and regulatory support to domestic firms—including state-owned enterprises and privately owned national champions.

These policies are a central pillar of China’s long-term economic strategy to move up the value chain and dominate high-tech industries, both domestically and globally. Signature initiatives include the 2006 “Medium-to Long-Term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology” and the 2015 “Made in China 2025” plan.

As reiterated in the 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025), China’s strategic focus sectors include:

- Advanced information technology

- Automated machine tools and robotics

- Aviation and spaceflight equipment

- Maritime engineering and high-tech vessels

- Advanced rail transit equipment

- New energy vehicles (NEVs)

- Power equipment

- Agricultural machinery

- New materials

- Biopharmaceuticals and advanced medical devices

While these initiatives are presented as industrial modernization efforts, in practice they form part of a broader strategy of “indigenous innovation,” aimed at replacing foreign technologies, products, and services with domestic alternatives. This strategy typically unfolds in three phases: (1) acquisition or development of Chinese-owned technology and IP, (2) substitution of foreign offerings in the domestic market, and (3) expansion into global markets—often supported by state financing and regulatory advantages. Foreign companies engaged in target sectors are frequently welcomed to invest, manufacture, and conduct research and development in China, and may receive generous government incentives to do so. Once China has managed to develop its own domestic industry, however – with foreign capital, intellectual property, and human resources playing a significant role – foreign companies can find themselves quickly pushed back out of the market, unable to compete with emerging, state-supported domestic competitors.

China’s approach increasingly relies on non-transparent subsidies, opaque central and local government guidance funds (reportedly exceeding $500 billion), and localized standards-setting, all of which create systemic disadvantages for foreign firms. A 2022 report by the Center for Strategic & International Studies found that China’s industrial policy support in 2019 was approximately four times higher than the United States’ relative to GDP, illustrating the scale and market distorting effect of these interventions. Even ostensibly neutral policies may be applied in a discriminatory manner, particularly at the provincial and local levels.

Although references to Made in China 2025 have diminished publicly, the strategy’s objectives remain intact and are now actively pursued through frameworks such as Strategic Emerging Industries, China Standards 2035, and sector-specific initiatives like the New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2021–2035).

U.S. firms should be prepared for policy-driven market distortions, rising compliance costs, IP-related risks, and opaque regulatory enforcement. Effective China strategies should include robust due diligence, risk mitigation planning, local stakeholder engagement, and continuous monitoring of evolving policy trends at both the central and sub-central levels.

For more information, please refer to the USTR 2025 National Trade Estimate Report.